Over the last twenty years, the global economic model has been under stress as more and more people around the world have come to recognise that the benefits of the economic model are very unevenly distributed. However, it is only in the last ten years since the collapse of the global banking sector that we have seen political shifts towards nationalism, isolationism, and extremism. Pundits, especially in the media, have fanned the nationalistic flames, and generally drawn the wrong conclusions as to the cause of the problem. In this essay, Alasdair White argues that all the ‘…isms’ are, in fact, the result of a desperate regression to the extremes of national culture.

Back in the early 1990s, empirical evidence came to light that, when faced with a severe shock or downturn, organisations with a strong organisational culture found it quickly abandoned, followed by a sharp regression to national cultures. The greater the shock, the greater the regression towards the extremes. At the time, there was little in the way of robust data or research on this phenomena, for example Hofstede’s ground-breaking work on national cultures, published in 1980, was only just coming into the wider non-academic word, and the GLOBE Project (House) had yet to be created. But even without such models it was obvious that such a regression had occurred as the result of a shock.

Such a shock occurred in 2007/2008 when the banking sector broke its operating model and basically crashed a major part of the world’s financial system. The result has been an extended period of economic hardship that has seen unemployment rise as a result of lack of finance and the deployment of technology, a radical shift in focus away from the cost-heavy manufacturing sector towards the service sector, and a decline in spending power as wages decline or stop, savings dry up or are rebuilt, and people stop spending. For many, this has been an opportunity to re-prioritise their financial objectives and make life-style decisions, but for others it has brought hardship.

Unsurprisingly, the threat to living standards, the threat to the economic operating model, and the general decline in discretionary disposable income across the entire developed world has bought people up short and a regression to the extremes of national cultures was, I suggest, almost inevitable. In the USA we have seen a regression to an extreme version of republicanism with its associated isolationism and protectionist policies. In the UK we have seen a rejection of collectivism, a breakdown in collaboration with its trading partners, and a sharp rise in extremist nationalistic tendencies: xenophobia and extreme anti-immigration is on the rise, authority of all types is being challenged, the ‘approval ratings’ of all shades of politician are at a very low level, and there has been an increase in the ‘me’ culture, a decline in the willingness to help others, and a rejection of supranational groupings. In Europe, after an initial rise in nationalistic politics, people have rejected the political elites and reverted to more localised groupings, and have reaffirmed their belief in strong supranational institutions such as the EU. People from the developing economies of Africa and the near East, fleeing the depressed economic opportunities in their own countries, have headed for the EU in worrying numbers.

All these trends and events are, I suggest, symptomatic of cultural shock and represent a significant reversion to the more extreme ends of national cultures. Let me explore this idea by using Hofstede’s 6-D Cultural Model to examine the UK’s decision to leave the EU.

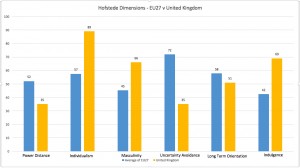

A discussion of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions can be found at https://www.geert-hofstede.com/national-culture.html. In the graphic above, the UK (the right-hand column in each dimension) is compared to the average score of the rest of the EU-27 excluding Cyprus for which there is no meaningful data. As can be seen, the EU-27 average suggests that a significant difference exists between the UK and the rest of the EU in five out of the six dimensions.

When viewed through the prism of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions, the United Kingdom is a society with a low tolerance of hierarchical power and a strong tendency to question authority structures resulting in a society which, as Hofstede puts it ‘…believes that inequalities amongst people should be minimized’. At the same time, the UK is highly individualistic in that its people are expected to find happiness through individual fulfilment, which has given rise to a rampant self-centred consumer culture that appears to be based on greed (conspicuous consumption). According to Hofstede, the culture is success-orientated and driven by competition and achievement, with success being defined as being the winner or best in field. The low uncertainty avoidance score indicates that the UK is happy with ambiguity and is willing to ‘make it up as they go along’; this is reflected in their lack of detail-orientation in which the end objective is clear enough but the ‘how’ only emerges within a changing environment. Finally, the UK generally possesses a positive attitude and a tendency towards optimism.

On the other hand, the rest of the EU is comfortable with hierarchies and power structures, and does not particularly feel that inequalities between peoples should be minimized. However, they have a significant tendency towards a collectivist approach in which people, as Hofstede puts it, belong in groups that will take care of them in exchange for loyalty, a fact borne out by the low masculinity score that indicates that quality of life and blending in are a sign of success. This can be expressed as ‘liking what you do’ as being more important than wanting to be the best. When it comes to uncertainty avoidance, it is clear that the rest of the EU feels threatened by ambiguity and the anxiety it brings, and has constructed concepts and institutions, such as the EU itself, to try to minimize these. As a result, these societies accept the need for restraint in terms of their individual desires and impulses.

This comparison suggests that the way the cultures of the UK and those in the EU-27 have developed and evolved have resulted in there being strong and definite cultural differences between them. Indeed, the question that comes to mind is how and why did the UK and the EU ever think they could get along – perhaps Brexit is an inevitable divorce driven by the clearly quite different objectives and cultural qualities of the two parties. The ‘shocks’ emanating from the financial sector collapse in 2007-2009 have, I contend, acted as a catalyst, and caused the UK and the EU to regress to their more extreme cultural positions.

This significant set of differences between the UK and the EU-27 will now play out in the Brexit negotiations. The UK will focus on ‘winning’ the negotiations and getting ‘what’s best for Britain’ without a care for what is in the best interests of both parties. This win-lose strategy is going to be confrontational and is likely to result in a deal that neither side wants, one in which the UK is more likely to be the long-term loser and will find itself marginalised. The UK media will, undoubtedly, present this as the EU seeking to humiliate and punish the UK and, as they have done for as long as the UK has been in the EU, they will go on about the unelected bureaucrats acting in an undemocratic manner towards a democratically mandated government, thus primarily demonstrating their own lamentable ignorance about how the EU works. Undoubtedly this will play well in the eyes of those seeking a UK exit from the EU, but it merely demonstrates how under-informed both the media and the ‘leavers’ really are about what is happening.

The EU-27 position will be that the UK will need to step back from confrontation and to negotiate in a collaborative way, respecting the opinion of others and recognising that the EU-27 is by far a bigger enterprise than the UK and will act in its collective best interests. The UK will have to meet its collective obligations and recognise that it will not be able to ride rough-shod over others to obtain its own way. While the UK will be negotiating with a win-lose strategy, the EU will be seeking a win-win, and the outcome may well be a lose-lose.

Does it have to be this way? Of course not, but the individualistic, competitive and greed-driven UK politicians are unlikely to allow cooler heads to prevail. The loose cannons amongst the ministerial Brexiteers: David Davis, Boris Johnson, Liam Fox, egged on by the right-wing UKIP demagogue, Nigel Farage, will need to be reeled in and silenced while the ‘hard Brexit’ PM, Theresa May, will need to step back and allow the professionals to deploy a well thought through strategy that has a detailed plan backing it. Instead, what is more likely to happen is that the politicians will make up policy on the hoof in the name of retaining flexibility. All this will be anathema to the EU-27 negotiators who will have serious trouble accepting the resulting ambiguity and the UK’s constantly changing objectives and policies: they will want clarity and certainty and a linear, step-by-step approach.

Already, the Brexiteers are putting out smoke, claiming that at the end of the two-year period the UK may just have to walk away without a deal. This is, of course, not a practical solution for the UK as they will then have the worst of everything: no trade deal with their biggest trading partner, no trade deals with the rest of the world, and a reputation for not abiding by the terms of the treaties and contracts they have entered into, thus labelling themselves unreliable trading partners with little or no respect for the law. The EU-27 will, on the other hand, be left with a political and organisational mess, and the increased likelihood that other disgruntled countries will also seek to go it alone. Voilà, everyone’s a loser.

This divorce maybe inevitable but it doesn’t have to be divisive. So instead of regressing to the extremes of national culture, everyone needs to start thinking more clearly about their own enlightened self-interest in what is an interconnected global environment – one that is distinctly more collaborative (in national cultural terms) than the individualistic and self-centred British seem to believe.

Alasdair White is a lecturer in Behavioural Economics at UIBS, a private business school with campuses in Brussels and Antwerp, as well as Spain, Switzerland and Japan. He is the internationally respected and much cited author of a number of business and management books and papers, and a historian and authority on the Napoleonic era.